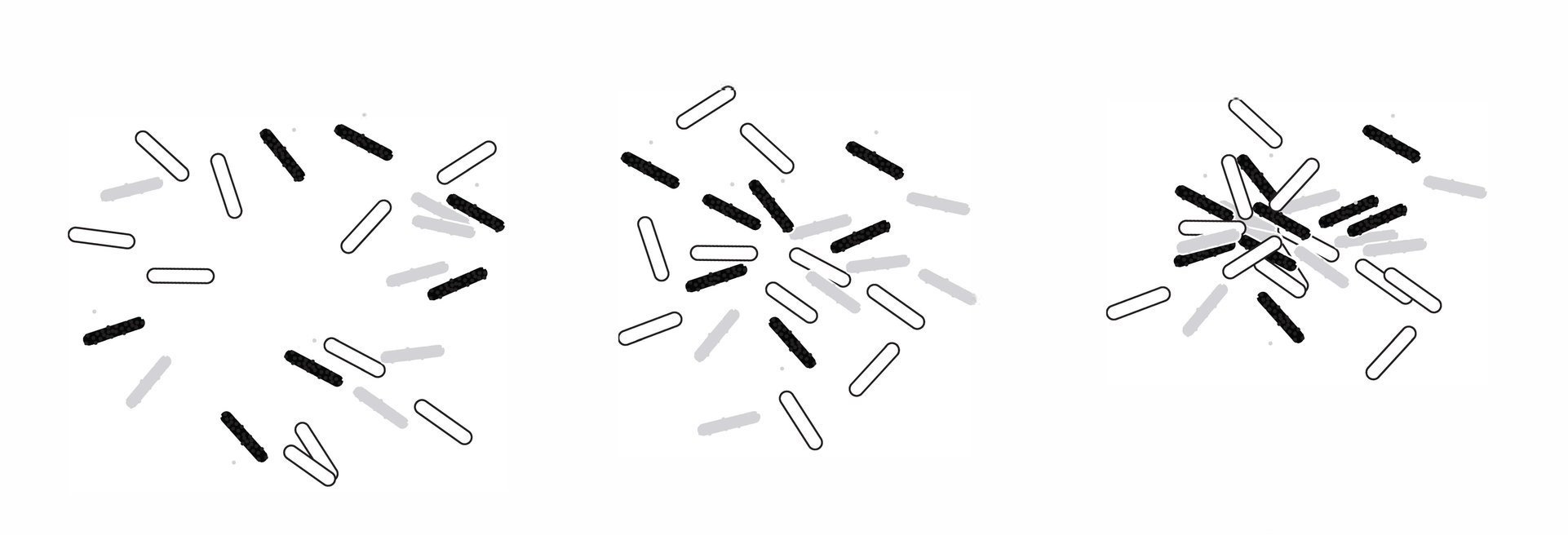

fruiting bodies move steadily towards resistance, 2021

dear world, the ability to exist as more than one entity, is what defines us.

not all unicellular life is unicellular

social motility: the 1980’s evolutionary biology movement sought to define us

queering: non-hierarchical social structures requiring systemic morphing, queering

existing as singular and a collective

The fruiting bodies of itselves: queer science studies writers

such as Octavia Butler use they/them pronouns in depicting us

“Having the remarkable property of existing alternatively as existing singularly or collectively, the single cells are self sufficient, but when under stress, go through internal changes that lead to aggregation in fruiting bodies”

-Evelyn Fox Keller

Who am i? Am I a aggregate? A single facet? Or many?

As a queer, chronically ill artist that looks towards material research to provide answers for more just, planetary balanced systems, I’m deeply inspired by Octativa Butler’s writing process. My book, ‘fruiting bodies move steadily towards resistance’ (transfer printed on paper waste) and below associated research are the month-long result of examining the Octavia E. Butler Archive Collection at Huntington Library and collectively- informed, decentralized technology precedents already modeled in nature. At this time in my artistic journey, I’m increasingly concerned by the role science will play in AI and other assistive technologies that shape our built environment and juxtapose Butler’s archives with material research of how nature inherently models technology. As of 2025, Butler’s own community and setting for Parable of the Sower where she wrote of fires in early 2025 decimating Altadena has come to fruition.

“Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction. All organizing is science fiction” says Octavia's Brood’s author, Walidah Imarisha. Struggle and speculation are one of the oldest iterations of symbiosis. Speculative or science fiction offers creative cytoskeletons for developing industries like movement organization, art and biodesign. The genre can be a crash-pad for imagining the worst of current injustices amplified on future technologies and scales or used as representation for marginalized people to create a space where current structures engineered for oppression are turned on its head.

Butler wrote of a world where our otherness can be our greatest tactic for survival, based on the foundation others before us have dreamt of. In an essay, by queer science theorist Aimee Bahng, entitled Plasmodial Improprieties: Octavia E. Butler, Slime Molds, and Imagining a Femi-Queer Commons the influence of slime molds on Butler is analyzed. An unearthed New Years 1988 note from a collection cataloging slime molds and colony organisms like angler fish and Portuguese man o’war in Butler’s archive says: “We find true colony organisms rare and fascinating. Here they are the exception, there, perhaps the rule” (Bahng). Butler studies the mechanics of slime molds acting as a social amoeba with separate parts morphing into a multicellular slug when food supply is exhausted or in conditions of scarcity in order to collectively or individually survive. Questioning slime molds defiance of taxonomy as it can not adhere to one category, Butler explores the flipping of exceptions and rules. Presenting queer ideology, Butler bends singular and plural grammar concepts to accommodate the nonconforming Ooloi form in Butler’s Lilith’s Brood Trilogy. Within writing notes of queer alienation, Butler flagged prominent research in her archives to build off of such as symbiosis theories of biologists Lynn Margulis and Evelyn Fox Keller. I found Butler’s inclusion of Keller’s1980 work on slime molds that rejected patriarchal patterns of the science community fascinating as Keller has credited the work’s inspiration to a paper she found of Alan Turing which suggested a dipole of generated spatial structure that could give rise to a morphing in the genetics in such structures. Butler didn’t just research on what she felt she wasn’t adequate in speaking on. Butler went further to build on the resources of queer science writers who have long spoken out despite alienation and assignment of otherness to articulate the same theories she was enthralled in. In this way, Butler has pioneered practices of non-hierarchical organization of knowledge and implemented it within her work for future implications to bloom.

Butler’s practices of speculation and dreaming bridges science and art speak directly to the power of decentralized organization based in collective knowledge. In the context of the built environment, architects and city planners can imagine diverse ecosystems that usually do not cohabitate such as introducing micro swamp street gutter systems in neighborhoods in communities with Tier 1 combined sewer overflow problems. There is so much to take from the ideology of Octavia Butler to inform the new age of biodesign, but we must leave room for a mutinied of minds to give constructive criticism on what we speak on or assign as weakness in the name of evolution.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of Octavia E. Butler.